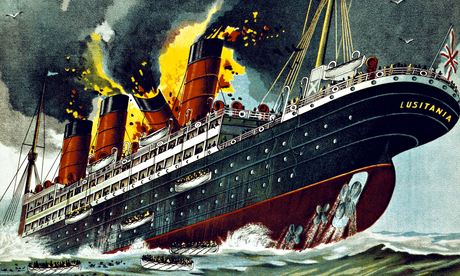

The sinking of the Lusitania as depicted in a propaganda poster to encourage new recruits. Photograph: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

One of the great mysteries of the first world war – whether or not the passenger ship Lusitania was carrying munitions and therefore a legitimate target when it was sunk by a German submarine in May 1915 – has been solved in the affirmative by newly released government papers. They contain Foreign Office concerns that a 1982 salvage operation might "literally blow up on us" and that "there is a large amount of ammunition in the wreck, some of which is highly dangerous".

Yet the truth was kept hidden in 1915 because the British government wanted to use the sinking of a non-military ship, and the loss of 1,198 lives, as an example of German ruthlessness. It was also a useful means of swaying American opinion in favour of entering the war. It eventually had the desired effect – the US declared war on Germany in April 1917 – but the lie continued as successive governments, worried about their ongoing relations with America, denied there were munitions on board.

These wartime lies are inevitable. The perpetrators – politicians, civil servants and soldiers – would argue that the end justifies the means, and that information that assists the enemy must remain secret. After the conflict, however, it's all about protecting reputations.

Take the case of the Sèvres protocol, the secret deal between the governments of Israel, France and the UK to topple President Nasser of Egypt by launching a two-step invasion in 1956 (otherwise known as "the Suez crisis"). Although reports of the deal leaked out within days, Sir Anthony Eden, the British prime minister, always denied its existence and even sent a civil servant to France to collect all copies and leave no trace. Yet the proof of Eden's engineered war remained buried until 1996 when a BBC documentary on the 40th anniversary of the Suez crisis obtained a copy from a former head of the Mossad (Israel's foreign intelligence service).

My own research into the case of the Salerno mutineers – 191 veterans of the Eighth Army who were convicted of mutiny for refusing to join unfamiliar units at the Salerno beachhead in 1943 – turned up documents that proved they had been lied to and were probably victims of a miscarriage of justice.

Of course many, if not most, "smoking guns" have yet to be discovered. The two Australian officers – lieutenants "Breaker" Morant and Handcock – executed by the British for shooting unarmed Boer prisoners during the South African war of 1899-1902 always claimed they were following verbal orders approved by their commander-in-chief, Sir Herbert Kitchener. Those orders, they said, were to execute any Boers captured in British khaki. But when a member of Kitchener's staff denied this at their trial, their fate was sealed. Did he lie because peace talks with the Boers were under way? It is possible, but documentary evidence will be hard to find (as Australian campaigners know to their cost).

Which makes the news that diaries and documents belonging to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini might be hidden near the Swiss border another tantalising prospect. The documents are said to include important state papers that Mussolini hoped to use in negotiating his surrender with the Allies, and should reveal many of wartime Italy's secrets. But we have been here before – with the fake Hitler diaries – and will have to be cautious if they are ever found.

Does all this matter? Do we need to know the truth? The answer is yes. We can forgive the lies at the time – many are often told without malice and, at least in theory, in the national interest – but they must at some point be publicly acknowledged. We need to know why governments (and individuals) take the decisions they do. That, to me, is the point of history.

P.S. great/important find by Fulford

Replies

All wars are based on trumped-up lies.

indeed