Inca can be spelled Inka and was known as Tiwantinsuya.

As ancient civilizations sprang up across the planet thousands of years ago, so too the Inca civilization evolved. As with all ancient civilizations, its exact origins are unknown. Their historic record, as with all other tribes evolving on the planet at that time, would be recorded through oral tradition, stone, pottery, gold and silver jewelry, and woven in the tapestry of the people.

The Inca of Peru have long held a mystical fascination for people of the western world. Four hundred years ago the fabulous wealth in gold and silver possessed by these people was discovered, then systematically pillaged and plundered by Spanish conquistadors. The booty they carried home altered the whole European economic system. And in their wake, they left a highly developed civilization in tatters. That a single government could control many diverse tribes, many of which were secreted in the most obscure of mountain hideaways, was simply remarkable.

No one really knows where the Incas came from that historic record left in stone for archaeologists to unravel through the centuries that followed.

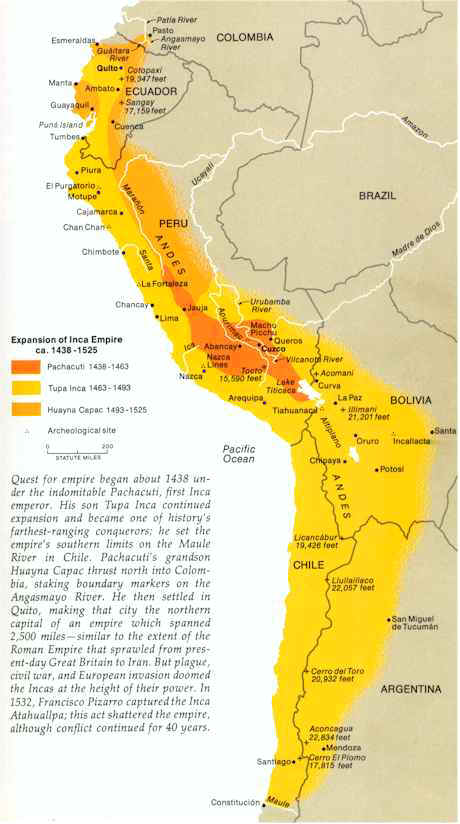

The Inca Empire was quite short-lived. It lasted just shy of 100 years, from ca.1438 AD, when the Inca ruler Pachacuti and his army began conquering lands surrounding the Inca heartland of Cuzco, until the coming of the Spaniards in 1532.

In 1438 the Inca set out from their base in Cuzco on a career of conquest that, during the next 50 years, brought under their control the area of present-day Peru, Bolivia, northern Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Within this area, the Inca established a totalitarian state that enabled the tribal ruler and a small minority of nobles to dominate the population.

Most of the accounts agree on thirteen emperors. The Inca emperors were known by various titles, including "Sapa Inca," "Capac Apu," and "Intip Cori." Often, an emperor was simply referred to as The Inca.

The first seven were legendary, local, and of slight importance. During this period the Inca were a small tribe, one of many, whose domain did not extend many miles around their capital city, Cuzco. They were warriors, almost constantly at war with neighboring tribes. Ritual sacrifices were common, evidence of which is found by archaeologists to this very day.

Cusco was the center of the Inca Empire, with its advanced hydraulic engineering, agricultural techniques, marvelous architecture, textiles, ceramics and ironworks.

1. Manco Capac - Sun God

2. Sinchi Roca

3. Lloque Yupanqui

4. Maita Capac

5. Capac Yupanqui

6. Inca Roca

7. Yahuar Huacac

8. Inca Viracocha

9. Pachacuti-Inca-Yupanqui

10. Topa Inca Yupanqui

11. Huayna Capac

12. Huascar

13. Atahuallpa

The incredibly rapid expansion of the Inca Empire began with Viracocha's son Pachacuti, who was one of the great conquerors, and one of the great men in the history of the Americas. With his accession in 1438 AD reliable history began, almost all the chroniclers being in practical agreement.

Pachacuti was called considered the greatest man that the aboriginal race of America has produced. He and his son Topa Inca were powerful rulers conquering many lands as they built ther kingdom.

Pachacuti was a great civic planner as well. Tradition ascribes to him the city plan of Cuzco as well as the erection of many of the massive masonry buildings that still awe visitors at this this ancient capital.

Plan of attack

The Aymara-speaking rivals in the region of Lake Titicaca, the Colla and Lupaca, were defeated first, and then the Chanca to the west. The latter attacked and nearly captured Cuzco. After that, there was little effective resistance. First the peoples to the north were subjugated as far as Quito, Ecuador, including the powerful and cultured kingdom of Chimú on the northern coast of Peru. Topa Inca then took over his father's role and turned southward, conquering all of northern Chile as far as the Maule River, the southernmost limit of the empire. His son, Huayna Capac, continued conquests in Ecuador to the Ancasmayo River, the present border between Ecuador and Colombia.

The Incans gave their empire the name, 'Land of the Four Quarters' or the Tahuantinsuyu Empire. It stretched north to south some 2,500 miles along the high mountainous Andean range from Colombia to Chile and reached west to east from the dry coastal desert called Atacama to the steamy Amazonian rain forest.

The Incas ruled the Andean Cordillera, second in height and harshness to the Himalayas. Daily life was spent at altitudes up to 15,000 feet and ritual life extended up to 22,057 feet to Llullaillaco in Chile, the highest Inca sacrificial site known today. Mountain roads and sacrificial platforms were built, which means a great amount of time was spent hauling loads of soil, rocks, and grass up to these inhospitable heights. Even with our advanced mountaineering clothing and equipment of today, it is hard for us to acclimatize and cope with the cold and dehydration experienced at the high altitudes frequented by the Inca. This ability of the sandal-clad Inca to thrive at extremely high elevations continues to perplex scientists today.

At the height of its existence the Inca Empire was the largest nation on Earth and remains the largest native state to have existed in the western hemisphere. The wealth and sophistication of the legendary Inca people lured many anthropologists and archaeologists to the Andean nations in a quest to understand the Inca's advanced ways and what led to their ultimate demise.

The Incas had an incredible system of roads. One road ran almost the entire length of the South American Pacific coast! Since the Incas lived in the Andes Mountains, the roads took great engineering and architectural skill to build. On the coast, the roads were not surfaced and were marked only by tree trunks The Incas paved their highland roads with flat stones and built stone walls to prevent travelers from falling off cliffs.

Referred to as an 'all-weather highway system', the over 14,000 miles of Inca roads were an astonishing and reliable precursor to the advent of the automobile. Communication and transport was efficient and speedy, linking the mountain peoples and lowland desert dwellers with Cuzco. Building materials and ceremonial processions traveled thousands of miles along the roads that still exist in remarkably good condition today. They were built to last and to withstand the extreme natural forces of wind, floods, ice, and drought.

This central nervous system of Inca transport and communication rivaled that of Rome. A high road crossed the higher regions of the Cordillera from north to south and another lower north-south road crossed the coastal plains. Shorter crossroads linked the two main highways together in several places.

The terrain, according to Ciezo de Leon, an early chronicler of Inca culture, was formidable. The road system ran through deep valleys and over mountains, through piles of snow, quagmires, living rock, along turbulent rivers; in some places it ran smooth and paved, carefully laid out; in others over sierras, cut through the rock, with walls skirting the rivers, and steps and rests through the snow; everywhere it was clean swept and kept free of rubbish, with lodgings, storehouses, temples to the sun, and posts along the way.

The Incas did not discover the wheel, so all travel was done on foot. To help travelers on their way, rest houses were built every few kilometers. In these rest houses, they could spend a night, cook a meal and feed their llamas.

Their bridges were the only way to cross rivers on foot. If only one of their hundreds of bridges was damaged, a major road could not fully function; every time one broke, the locals would repair it as quickly as possible.

Inca society was made up of ayllus, which were clans of families who lived and worked together. Each allyu was supervised by a curaca or chief. Families lived in thatched-roof houses built of stone and mud. Furnishings were unkown with families sitting and sleeping on the floor. Potatoes were a basic Inca food. The Imperial Incas clothed themselves in garments made from Alpaca and many of their religious ceremonies involved the animal. They wore sandals on their feet.

In Inca social structure, the ruler, Sapa Inca, and his wives, the Coyas, had supreme control over the empire. The High Priest and the Army Commander in Chief were next. Then came the Four Apus, the regional army commanders. Next were temple priests, architects, administrators and army generals. Next were artisans, musicians, army captains and the quipucamayoc, the Incan accountants. At the bottom were sorcerers, farmers, herding families and conscripts.

Inca society continued uninterrupted in this way for hundreds of years. The appearance of light-skinned strangers during the rule of Atahuallpa, however, was to forever change things for the Inca. Deadly plague would soon sweep through the Inca empire. Those that survived had to face the swords and cannons of the invading Spanish. After leading the Spanish to more gold than they had ever before seen, even Lord Atahuallpa was strangled by his Spanish captors.

Every style of hand-weaving was practiced by the Incas. They used this instead of writing in some cases. They also made very artistic pottery.

Music was part of ceremony. Incas knew how to smelt and cast metals so they made many different types of instruments such as trumpets and bells out of materials such as brass or stone.

At its peak, Ican society had more than six million people. As the tribe expanded and conquered other tribes, like the Paracas, the Incans began to consolidate their empire by integrating not only the ruling classes of each conquered tribe but also developing a universal language, calling it Quechua (pronounced KECH-WUN).

This ubiquitous integration encompassed the histories, myths and legends of each subject tribe; stories being intentionally combined, adopted or obliterated, or just accidentally confused. This practice was characteristic of the Incans quest for organization and structure. The Amautas, a special class of wise men who perpetuated traditions of the people, history and legend, redefined myths where and when necessary to establish miracles of faith or precedent or sanctions.

The Incan language was based on nature. All of the elements of which they depended, and even some they didn't were give a divine character. They believed that all deities were created by an ever-lasting, invisible, and all-powerful god named Wiraqocha, or Sun god. The King Incan was seen as Sapan Intiq Churin, or the Only Son of the Sun.

The Inca were a deeply religious people. They feared that evil would befall at any time. Sorcerors held high positions in society as protectors from the spirits. They also believed in reincarnation, saving their nail clippings, hair cuttings and teeth in case the returning spirit needed them.

The religious and societal center of Inca life was contained in the middle of the sprawling fortress known as Sacsahuaman. Here was located Cuzco, 'The Naval of the World' [we call it the Solar Plexus] - the home of the Inca Lord and site of the sacred Temple of the Sun. At such a place the immense wealth of the Inca was clearly evident with gold and silver decorating every edifice. The secret of Inca wealth was the mita. This was a labor program imposed upon every Inca by the Inca ruler. Since it only took about 65 days a year for a family to farm for its own needs, the rest of the time was devoted to working on Temple-owned fields, building bridges, roads, temples, and terraces, or extracting gold and silver from the mines. The work was controlled through chiefs of thousands, hundreds and tens.

The Incas worshipped the Earth goddess Pachamama and the sun god, the Inti. The Inca sovereign, lord of the Tahuantinsuyo, the Inca empire, was held to be sacred and to be the descendant of the sun god. Thus, the legend of the origin of the Incas tells how the sun god sent his children Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo (and in another version the four Ayar brothers and their wives) to found Cuzco, the sacred city and capital of the Inca empire.

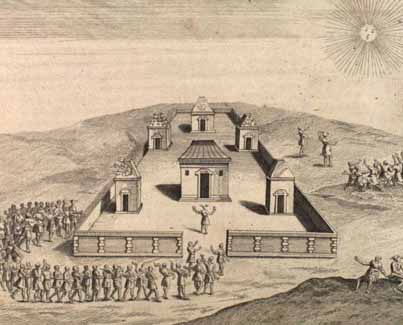

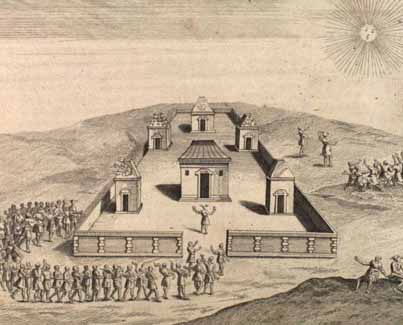

Inti Raymi, the feast of the sun The "Inti Raymi" or "Sun Festivity" was the biggest, most important, spectacular and magnificent festivity carried out in Inca times. It was aimed to worship the "Apu Inti" (Sun God). It was performed every year on June 21, that is, in the winter solstice of the Southern Hemisphere, in the great Cuzco Main Plaza.

In the Andean mythology it was considered that Incas were descendants of the Sun, therefore, they had to worship it annually with a sumptuous celebration. More over, the festivity was carried out by the end of the potato and maize harvest in order to thank the Sun for the abundant crops or otherwise in order to ask for better crops during the next season.

Besides, it is during the solstices when the Sun is located in the farthest point from the earth or vice versa, on this date the Quechuas (native people of the Andes who speak "quechua" language) had to perform diverse rituals in order to ask the Sun not to abandon its children.

Preparations had to be carried out in the Koricancha (Sun Temple), in the Aqllawasi (House of Chosen Women), and in the Haukaypata or Wakaypata that was the northeastern sector of the great Main Square. Some days before the ceremony, all the population had to practice fast and sexual abstinence. Before dawn on June 21st the Cusquenian nobility, presided over by the Inca and the Willaq Uma (High Priest), were located on the Haukaypata (the Plaza's ceremonial portion), the remaining noble population were placed on the Kusipata (southwestern portion). Prior to this the "Mallki" (mummies of noble ancestors) were brought and they were located in privileged sectors so that they could witness the ceremony.

At sunrise, the population had to greet the Sun God with the "much'ay" ("mocha" in its Spanish form) sending forth-resounding kisses offered symbolically with the fingertips. After all that, people sang in tune solemn canticles in a low voice that later were transformed into their "wakay taky" (weepy songs), arriving like this to an emotional and religious climax.

Subsequently, the Son of the Sun (the Inca king), used to take in his two hands two golden ceremonial tumblers called "akilla" containing "Aqha" (chicha = maize beer) made inside the Aqllawasi. The beverage of the tumbler in the right hand was offered to the Sun and then poured into a golden channel communicating the Plaza with the Sun Temple. The Inca drank a sip of chicha from the other tumbler, the remaining was then drank in sips by the noblemen close to him. Later, chicha was offered to every attendant.

Some historians suggest that this ceremony was started inside the Coricancha in presence of the Sun representation that was made of very polished gold that at the sunrise was reflected with a blinding brilliance. Later the Inca, along with his retinue, went toward the great Plaza through the "Intik'iqllu" or "Street of the Sun" (present-day Loreto street) in order to witness the llama sacrifice.

During this most important religious ceremony in Incan times, the High Priest had to perform the llama sacrifice offering a completely black or white llama. With a sharp ceremonial golden knife called "Tumi" he had to open the animal's chest and with his hands pulled out its throbbing heart, lungs and viscera, so that observing those elements he could foretell the future. Later, the animal and its parts were completely incinerated.

After the sacrifice, the High Priest had to produce the Sacred Fire. Staying in front of the Sun he had to get its rays in a concave gold medallion that contained some soft or oily material in order to produce the fire that had to be kept during next year in the Koricancha and Aqllawasi.

Subsequently the priests offered the Sanqhu that was something like "holy bread" prepared from maize flour and blood of the sacrificed llama; its consumption was entirely religious as a Christian host is.

Once that all ritual stages of the Inti Raymi were finished, all the attendants were located in the southwestern Plaza's sector named Kusipata (Cheer Secto" present-day Plaza del Regocijo) where after being nourished, people were entertained with music, dances and abundant chicha.

Nowadays, the Inti Raymi is staged annually in Saqsaywaman on June 24th with the participation of hundreds of actors wearing typical outfits. It's a great opportunity to imagine the life at the Incas time.

Not many people lived in the Incan cities. People lived in the nearby villages and traveled into town for festivals or business.

The city was mainly used for the government. All the records for nearby villages were reported by their leaders and recorded in the city by the quipucamayoc. About the only people who lived in the city were the metalworkers, carpenters, weavers and other crafters who made artwork for the temples. These people lived in the artisans' quarters. Outside of the cities were the government storehouses and soldiers' barracks.

In every major Inca city, the Sapa Inca had a palace for use when he visited the city. On those grounds were the convents for the Sun Virgins and houses for servants. The buildings on the grounds were single storied edifices, built of stone with a thatched grass roof. Their only entrance was to the courtyard that they were on.

Everyone worked except for the very young and the very old. Children worked by scaring away animals from the crops and helping in the home.

About 2/3 of a farmer's goods would be shared by a tax system, and the rest were for keeps. Some of the goods would be distributed to others, goods would be received in return, and the rest was stored in government storehouses or sacrificed to the gods.

Each ayllu - clans - had their own self-supporting farm community. Ayllu members worked the land cooperatively to produce food crops and cotton. All work was done by hand because the Incas lacked wheeled tools and draft animals. Their simple implements included a heavy wooden spade or foot plow called a taclla, a stone-tipped club to break up clods, a bronze-bladed hoe, and a digging stick.

The inhabitants of the Andean region developed more than half the agricultural products that the world eats today. Among these are more than 20 varieties of corn; 240 varieties of potato; as well as one or more varieties of squash, beans, peppers, peanuts, and cassava (a starchy root); and quinoa, which is made into a cereal.

By far the most important of these was the potato. They grew over 20 varieties of corn and 240 varieties of potatoes.The Incas planted the potato, which is able to withstand heavy frosts, as high as 4600 m (15,000 ft). At these heights the Incas could use the freezing night temperatures and the heat of the day to alternately freeze and dry the potatoes until all the moisture had been removed. The Incas then reduced the potato to a light flour.

They cultivated corn up to an altitude of 4100 m (13,500 ft) and consumed it fresh, dried, and popped. They also made it into an alcoholic beverage known as saraiaka or chicha.

The Incas faced difficult conditions for agriculture. Mountainous terrain limited the land that could be used for agriculture, and water was sometimes scarce.

To compensate, the Incas adopted and improved upon the terracing methods invented by pre-Inca civilizations. They built stone walls to create raised, level fields. These fields formed steplike patterns along the sides of hills that were too steep to irrigate or plough in their natural state. Terraces created more arable land and kept the topsoil from washing away in heavy rains.

Although rain generally falls in the Andes between December and May, there are often years of drought. The Incas constructed complex canals to bring water to terraces and other patches of arable land.

They also made use of natural fertilizers. Guano, the nitrate-rich droppings of birds, was plentiful in coastal areas. In the highlands, farmers used the remains of slaughtered llamas as a fertilizer.

Camelids, such as llamas, alpacas, and vicuas, were very important to the economy. In addition to carrying burdens, llamas and alpacas were raised as a source of coarse wool and of dung, which was used for fuel. The finest-quality wool came from the wild vicua, which was caught, sheared, and set free again.

The Inca also raised guinea pigs, ducks, and dogs, which were the main sources of meat protein.

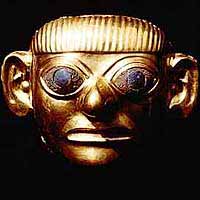

The Incas are famous for their gold. They mined extensive deposits of gold and silver, but this wealth ultimately brought disaster in the 16th century, when Spanish soldiers came seeking riches for themselves and their king.

Gold, to the Incas, was the 'sweat of the sun' and Silver the 'tears of the moon.'

Money existed in the form of work. Each subject of the empire paid taxes by laboring on the myriad roads, crop terraces, irrigation canals, temples, or fortresses. In return, rulers paid their laborers in clothing and food. Silver and gold were abundant, but only used for aesthetics.

The Incas had a highly organized government based in Cuzco. The emperor lived there and was regarded to as The Inca, the main supreme the ruler. Underneath him were the nobles.,They were talented and gifted and their skills provided for all of the Inca civilization.

Cuzco, which emerged as the richest city in the New World, was the center of Inca life, the home of its leaders. The riches that were gathered in the city of Cuzco alone, as capital and court of the Empire, were incredible, says an early account of Inca culture written 300 years ago by Jesuit priest Father Bernabe Cobo.

Inca kings and nobles amassed stupendous riches which accompanied them, in death, in their tombs. But it was their great wealth that ultimately undid the Inca, for the Spaniards, upon reaching the New World, learned of the abundance of gold in Inca society and soon set out to conquer it at all costs. The plundering of Inca riches continues today with the pillaging of sacred sites and blasting of burial tombs by grave robbers in search of precious Inca gold.

Because everyone had everything they needed, people rarely stole things. As a result, there were no prisons. The worst crimes in the Inca empire were murder, insulting the Sapa Inca and saying bad things about gods. The punishment, being thrown off of a cliff, was enough to keep most people from committing these crimes. Adultery with a Sun Virgin wasn't worth it. The couple was tied up by their hands and feet to a wall and left to starve to death. If one made love to one of the Inca's wives, they would be hung on a wall naked and left to starve. Smaller crimes were punished by the chopping off of the hands and feet or the gouging of the eyes.

The main form of communication between cities was the chasqui. The chasqui were young men who relayed messages. Say the army general in Nazca needs to report a village uprising to the Sapa Inca in Cuzco. One chasqui runner would start from the chasqui post in Nazca and run about a kilometer to another chasqui, waiting outside another hut. The message would be relayed and the chain would be continued for hundreds of miles by hundreds of runners until the last runner reached the Sapa Inca and told the message, exact to the original word, because a severe punishment awaited a wrong message, which they knew since their training began in boyhood.

Most historians agree that the Inca had a calendar based on the observation of both the Sun and the Moon, and their relationship to the stars. Names of 12 lunar months are recorded, as well as their association with festivities of the agricultural cycle.

There is no suggestion of the widespread use of a numerical system for counting time, although a quinary decimal system, with names of numbers at least up to 10,000, was used for other purposes. The organization of work on the basis of six weeks of nine days suggests the further possibility of a count by triads that could result in a formal month of 30 days.

A count of this sort was described by Alexander von Humboldt for a Chibcha tribe living outside of the Inca Empire, in the mountainous region of Colombia. The description is based on an earlier manuscript by a village priest, and one authority has dismissed it as holy imaginary, but this is not necessarily the case. The smallest unit of this calendar was a numerical count of three days, which, interacting with a similar count of 10 days, formed a standard 30-day month.

Every third year was made up of 13 moons, the others having 12. This formed a cycle of 37 moons, and 20 of these cycles made up a period of 60 years, which was subdivided into four parts and could be multiplied by 100. A period of 20 months is also mentioned. Although the account of the Chibcha system cannot be accepted at face value, if there is any truth in it at all it is suggestive of devices that may have been used also by the Inca.

In one account, it is said that the Inca Veracocha established a year of 12 months, each beginning with the New Moon, and that his successor, Pachacuti, finding confusion in regard to the year, built the sun towers in order to keep a check on the calendar. Since Pachacuti reigned less than a century before the conquest, it may be that the contradictions and the meagerness of information on the Inca calendar are due to the fact that the system was still in the process of being revised when the Spaniards first arrived.

Despite the uncertainties, further research has made it clear that at least at Cuzco, the capital city of the Inca, there was an official calendar of the sidereal-lunar type, based on the sidereal month of 27 1/3 days. It consisted of 328 nights (12X271/3) and began on June 8/9, coinciding with the heliacal rising (the rising just after sunset) of the Pleiades; it ended on the first Full Moon after the June solstice (the winter solstice for the Southern Hemisphere). This sidereal-lunar calendar fell short of the solar year by 37 days, which consequently were intercalated. This intercalation, and thus the place of the sidereal-lunar within the solar year, was fixed by following the cycle of the Sun as it strengthened to summer (December) solstice and weakened afterward, and by noting a similar cycle in the visibility of the Pleiades.

Intihuatana, the hitching post of the sun, is possibly the last remaining seasonal sun dials in Peru. The rest were destroyed by the Spaniards, who as Catholics, found them to be paganistic.

The Ancient Geometric Measure of Time in Tiwanaku

Kepler's Kinetic law and the Proportional Clock

Geometrizing of the Tiahuanacan Solar Cycle, may be a particularly useful line of enquiry into many other ancient prehistoric cultures. It may explain how informations on celestial calculations was recorded and complex astronomical knowledge was transmitted, by being inserted in the enormous architectonics and planimetric structures, still to be seen today in various parts of the world.

The scientific reliability of this research finds indirect confirmation on the clock dial, since all system of time measurement in fact refers to the solar cycle, that is to say to mathematical and geometrical parameters that describe the terrestrial orbit. Thus, by applying Kepler's second kinematic law to the hours circle, we arrive at a geometric system for the figurative representation of time known as the Proportional Dial.

The Proportional Clock derives in turn from this dial and incorporates a new figurative dimension of time in Architecture and Urban planning.

The demise of the Incan civilization, at the hands of the Spanish Conquistadors, occurred in the 1500's, after years of fighting left the already disarticulate anthology in more disarray.

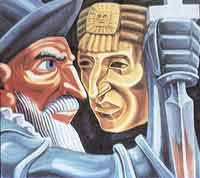

With the arrival from Spain in 1532 of Francisco Pizarro and his entourage of mercenaries or conquistadors, the Inca empire was seriously threatened for the first time. Duped into meeting with the conquistadors in a peaceful gathering, an Inca emperor, Atahualpa, was kidnapped and held for ransom. After paying over $50 million in gold by today's standards, Atahualpa, who was promised to be set free, was strangled to death by the Spaniards who then marched straight for Cuzco and its riches.

Ciezo de Leon, a conquistador himself, wrote of the astonishing surprise the Spaniards experienced upon reaching Cuzco. As eyewitnesses to the extravagant and meticulously constructed city of Cuzco, the conquistadors were dumbfounded to find such a testimony of superior metallurgy and finely tuned architecture. Temples, edifices, paved roads, and elaborate gardens all shimmered with gold.

By Ciezo de Leon's own observation the extreme riches and expert stone work of the Inca were beyond belief: "In one of (the) houses, which was the richest, there was the figure of the sun, very large and made of gold, very ingeniously worked, and enriched with many precious stones. They had also a garden, the clods of which were made of pieces of fine gold; and it was artificially sown with golden maize, the stalks, as well as the leaves and cobs, being of that metal.

Besides all this, they had more than twenty golden (llamas) with their lambs, and the shepherds with their slings and crooks to watch them, all made of the same metal. There was a great quantity of jars of gold and silver, set with emeralds; vases, pots, and all sorts of utensils, all of fine gold - it seems to me that I have said enough to show what a grand place it was; so I shall not treat further of the silver work of the chaquira (beads), of the plumes of gold and other things, which, if I wrote down, I should not be believed."

Much of the conquest was accomplished without battles or warfare as the initial contact Europeans made in the New World resulted in rampant disease. Old World infectious disease left its devastating mark on New World Indian cultures. In particular, smallpox spread quickly through Panama, eradicating entire populations. Once the disease crossed into the Andes its southward spread caused the single most devastating loss of life in the Americas. Lacking immunity, the New World peoples, including the Inca, were reduced by two-thirds.

In the years following the conquest, the only chroniclers of the Incan culture lacked the objectivity and scientific interests needed for accurate accounts. In addition, they all held to a rigid belief in the literal truth of Biblical records. Thus, much of the myths and legends were held in revulsion, as either trivial or immoral, and failed to reach the annals of Incan civilization.

Those myths that did survive may have been distorted or diluted by those Incans who chose to adapt their stories for the Spanish Christian ears. No conclusion can be made about this mysterious myth other than that is an intriguing and complicated culture, whose form of communication, albeit surreptitious, is innately beautiful.

With the aid of disease and the success of his initial deceit of Atahualpa, Pizarro acquired vast amounts of Inca gold which brought him great fortune in Spain. Reinforcements for his troops came quickly and his conquest of a people soon moved into consolidation of an empire and its wealth. Spanish culture, religion, and language rapidly replaced Inca life and only a few traces of Inca ways remain in the native culture as it exists today.

What remains of the Inca legacy is limited, as the conquistadors plundered what they could of Inca treasures and in so doing, dismantled the many structures painstakingly built by Inca craftsmen to house the precious metals. Remarkably, a last bastion of the Inca empire remained unknown to the Spanish conquerors and was not found until explorer Hiram Bingham discovered it in 1911.

He had found Machu Picchu a citadel atop a mountainous jungle along the Urubamba River in Peru. Grand steps and terraces with fountains, lodgings, and shrines flank the jungle-clad pinnacle peaks surrounding the site. It was a place of worship to the sun god, the greatest deity in the Inca pantheon.

Manco Capac, was the name of the last of the Inca rulers, and the son of Huayna Capac. Manco Capac was supposedly crowned (1534) emperor by the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro but was tolerated only as a puppet. He escaped, levieda huge army, and in 1536 laid siege to Cuzco, the Inca capital. The defense was commanded by Hernando Pizarro. Although the Incans had by now learned some European tactics of war they were outclassed by technical advantages. Manco Capac could not prevent dismemberment of his army at harvest time. The heroic siege, which virtually destroyed the city, was abandoned after ten months, but during the ensuing eight years the Inca's name became a terror throughout Peru. Manco Capac fought a bloody guerrilla war against soldiers and settlers. He was treacherously murdered in 1544, after giving refuge to the defeated supporters of Diego de Almagro, who had rebelled against Pizarro.

In 1541 the Wheel of Fortune turned against Francisco Pizarro, and the conquistador reaped a bit of what he had sown. After the fall of Cuzco in 1533, Pizarro and his brother cut their rival, Diego de Almagro, out of much of the booty. By way of compensation, Francisco offered him Chile, and the Spaniard marched off in hopes of conquest and gold. He returned two years later, having found no fortune, and helped suppress Manco. His quarrel with the Pizarros led to a battle between their factions at Las Salinas on April 26, 1538. Captured, the defeated Almagro was garroted on Hernando's order. Francisco, now governor, later stripped Almagro's son, also named Diego, of lands leaving him bankrupt.

The embittered young Almagro and his associates plotted to assassinate Francisco after mass on June 16, 1541, but Pizarro got wind of their plan and stayed in the governor's palace. While Pizarro, his half-brother Francisco Martín de Alcántara, and about 20 others were having dinner, the conspirators invaded the palace. Most of Pizarro's guests fled, but a few fought the intruders, numbered variously between seven and 25. While Pizarro struggled to buckle on his breastplate, his defenders, including Alcántara, were killed. For his part Pizarro killed two attackers and ran through a third. While trying to pull out his sword, he was stabbed in the throat, then fell to the floor where he was stabbed many times.

Alcántara's wife buried Pizarro and Alcántara behind the cathedral. He was reburied under main altar in 1545, then moved into a special chapel in the cathedral on July 4, 1606. Church documents from the verification process for remains of St. Toribio in 1661, however, note a wooden box inside of which was a lead box inscribed in Spanish: Here is the skull of the Marquis Don Francisco Pizarro who discovered and won Peru and placed it under the crown of Castile.

In 1891, on the 350th anniversary of Pizarro's death, a scientific committee examined the desiccated remains that church officials had identified as Pizarro. In their account in American Anthropologist 7:1 (January 1894), they concluded that the skull conformed to cranial morphology then thought to be typical of criminals, a result seen as confirming identification. A glass, marble, and bronze sarcophagus was built to hold the mummy, which was venerated by history buffs and churchgoers.

But in 1977, workers cleaning a crypt beneath the altar found two wooden boxes with human bones. One box held the remains of two children; an elderly female; an elderly male, complete; and an elderly male, headless; and some fragments of a sword. The other contained the lead box--inscribed as had been recorded in 1661--in which was a skull that matched postcranial bones of the headless man in the first box. A Peruvian historian, anthropologist, two radiologists, and two American anthropologists studied the remains. The man was a white male at least 60 years old (Pizarro's exact age was unknown; he was said to be 63 or 65 by contemporary historians) and 5'5" to 5'9" in height. He had lost most of his upper molars and many lower incisors and molars, had arthritic lipping on his vertebrae, had fracture his right ulna while a child, and had suffered a broken nose.

Examination of the remains indicated that the assassins did a thorough job. There were four sword thrusts to neck, the sixth and twelfth thoracic vertebrae were nicked by sword thrusts, the arms and hands were wounded from warding off sword cuts (a cut on the right humerus and two on the left first metacarpal; the right fifth metacarpal was missing altogether), a sword blade had cut through the right zygomatic arch, a thrust penetrated the left eye socket, a rapier or dagger went through the neck into the base of skull, and a pair of thrusts had damage the left sphenoid. The savage overkill suggests revenge as a motive rather than simple murder or death in battle.

The scholars concluded that these were indeed the remains of Francisco Pizarro. The two children might be Pizarro's sons who died young, the elderly female is possibly the wife of Alcantara, and the other elderly male Alcántara. The dried out body long thought to be Pizarro exhibited no sign of trauma as would be expected if it was indeed the corpse of the conquistador. They decided that the interloper was possibly a church official, and replaced the body with t

Replies