The first signs of complex society in Mesoamerica were the Olmecs anancient Pre-Columbian civilization living in the tropical lowlands ofsouth-central Mexico, in what are roughly the modern-day states ofVeracruz and Tabasco.The area is about 125 miles long and 50 miles wide (200 by 80 km), withthe Coatzalcoalcos River system running through the middle. These sitesinclude San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, Laguna de los Cerros, Tres Zapotes,and La Venta, one of the greatest of the Olmec sites. La Venta is datedto between 1200 BCE through 400 BCE which places the major developmentof the city in the Middle Formative Period. Located on an island in acoastal swamp overlooking the then-active Río Palma river, the city ofLa Venta probably controlled a region between the Mezcalapa andCoatzacoalcos rivers.

The Olmec domain extended from the Tuxtlas mountains in the west to thelowlands of the Chontalpa in the east, a region with significantvariations in geology and ecology. Over 170 Olmec monuments have beenfound within the area, and eighty percent of those occur at the threelargest Olmec centers, La Venta, Tabasco (38%), San LorenzoTenochtitlan, Veracruz (30%), and Laguna de los Cerros, Veracruz (12%).

Those three major Olmec centers are spaced from east to west across thedomain so that each center could exploit, control, and provide adistinct set of natural resources valuable to the overall Olmec economy.La Venta, the eastern center, is near the rich estuaries of the coast,and also could have provided cacao, rubber, and salt.San Lorenzo, at the center of the Olmec domain, controlled the vastflood plain area of Coatzacoalcos basin and riverline trade routes.

Laguna de los Cerros, adjacent to the Tuxtlas mountains, is positionednear important sources of basalt, a stone needed to manufacture manos,metates, and monuments. Perhaps marriage alliances between Olmec centershelped maintain such an exchange network.

The Olmec heartlandis an archaeological term used to describe an area in the Gulf lowlandsthat is generally considered the birthplace of the Olmec culture. Thisarea is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills,ridges, and volcanoes. The Tuxtlas Mountains rise sharply in the north,along the Gulf of Mexico's Bay of Campeche. Here the Olmecs constructedpermanent city-temple complexes at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta,Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. In this region, the firstMesoamerican civilization would emerge and reign from 1400-400 BCE.

The Olmec flourished during Mesoamerica's Formative period, dating roughly from 1400 BCE to about 400 BCE. Asthe first Mesoamerican civilization, they laid much of the foundationfor the civilizations that would follow. Their influence went beyondthe heartland - from Chalcatzingo, far to the west in the highlands ofMexico, to Izapa, on the Pacific coast near what is now Guatemala, Olmecgoods have been found throughout Mesoamerica during this period.

What we today call Olmec first appears within the city of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán,where distinctive Olmec features appear around 1400 BCE. The rise ofcivilization here was assisted by the local ecology of well-wateredalluvial soil, as well as by the transportation network that theCoatzacoalcos river basin provided.

This environment may be compared to that of other ancient centers ofcivilization: the Nile, Indus, and Yellow River valleys, andMesopotamia. This highly productive environment encouraged a denseconcentrated population which in turn triggered the rise of an eliteclass.

It was this elite class that provided the social basis for theproduction of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts thatdefine Olmec culture. Many of these luxury artifacts, such as jade,obsidian and magnetite, came from distant locations and suggest thatearly Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network inMesoamerica. The source of the most valued jade, for example, is foundin the Motagua River valley in eastern Guatemala, and Olmec obsidian hasbeen traced to sources in the Guatemala highlands, such as El Chayaland San Martín Jilotepeque, or in Puebla, distances ranging from 200 to400 km away (120 - 250 miles away) respectively.

The first Olmec center, San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 BCE at about the same time that La Ventarose to prominence. A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzomonuments also occurred circa 950 BCE, which may point to an internaluprising or, less likely, an invasion. The latest thinking, however, isthat environmental changes may have been responsible for this shift inOlmec centers, with certain important rivers changing course.

Following the decline of San Lorenzo, La Venta became the most prominentOlmec center, lasting from 900 BCE until its abandonment around 400BCE. La Venta sustained the Olmec cultural traditions, but withspectacular displays of power and wealth. The Great Pyramid was thelargest Mesoamerican structure of its time. Even today, after 2500 yearsof erosion, it rises 34 meters above the naturally flat landscape.Buried deep within La Venta, lay opulent, labor-intensive "Offerings":1000 tons of smooth serpentine blocks, large mosaic pavements, and atleast 48 separate deposits of polished jade celts, pottery, figurines,and hematite mirrors.

It is not known with any clarity what caused the eventual extinction ofthe Olmec culture. It is known that between 400 and 350 BCE, populationin the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, andthe area would remain sparsely inhabited until the 19th century.

This depopulation was likely the result of "very serious environmentalchanges that rendered the region unsuited for large groups of farmers",in particular changes to the riverine environment that the Olmecdepended upon for agriculture, for hunting and gathering, and fortransportation. Archaeologists propose that these changes were triggeredby tectonic upheavals or subsidence, or the silting up of rivers due toagricultural practices.

One theory for the considerable population drop during the TerminalFormative period is suggested by Santley and colleagues (Santley et al.1997) and proposes shifts in settlement location [relocation] due tovolcanism instead of extinction. Volcanic eruptions during the Early,Late and Terminal Formative periods would have blanketed the lands andforced the Olmecs to move their settlements.

Whatever the cause, within a few hundred years of the abandonment of thelast Olmec cities, successor cultures had become firmly established.The Tres Zapotes site, on the western edge of the Olmec heartland,continued to be occupied well past 400 BCE, but without the hallmarks ofthe Olmec culture. This post-Olmec culture, often labeled Epi-Olmec,has features similar to those found at Izapa, some 330 miles (550 km) tothe southeast.

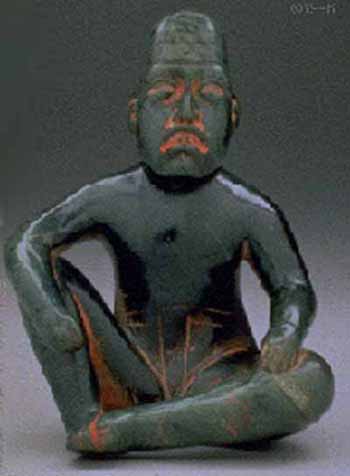

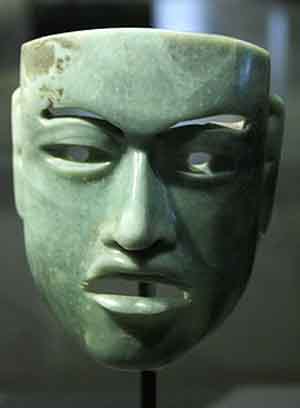

Olmec artforms emphasize both monumental statuary and small jadecarvings and jewelry. Much Olmec art is highly stylized and uses aniconography reflective of the religious meaning of the artworks. SomeOlmec art, however, is surprisingly naturalistic, displaying an accuracyof depiction of human anatomy perhaps equaled in the Pre-Columbian NewWorld only by the best Maya Classic era art.

Common motifs include downturned mouths and slit-like slanting eyes, both of which can be seen in most representations of "were-jaguars"or jaquar gods. The were-jaguar motif is characterized byalmond-shaped eyes, a downturned open mouth, and a cleft head. Thewere-jaguar supernatural incorporates the were-jaguar motif as well asother features, although various academics define the were-jaguarsupernatural differently.

The most well-known aspect of shamanism in Mesoamerican religion, and inthe whole of Native American shamanism, is the ability to assume thepowers of animals associated with the shaman. Such animals are called nahuales,and in Olmec art the most common of these is the jaguar. In a sense,the optimal spirit would have the spirituality and intellect of man andthe ferocity and strength of the jaguar, these are all combined in theshaman and his jaguar nahuale. The Jaguar Child may exemplifythis combination. This is a very common representation in Olmec art, andit often includes the slitted eyes and curved mouth pronounced in thisclose-up.

Olmec holds a half human-half jaguar baby.

Jade figure holding jaguar baby 1150-500 BC

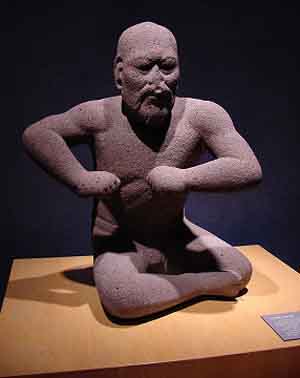

The Olmec culture was first defined as an art style, and this continuesto be the hallmark of the culture. Wrought in a large number of mediums jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone among others much Olmec art, suchas the Wrestler, is surprisingly naturalistic.

Other art, however, reveals fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, oftenhighly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning.Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of whichare seen in representations of were-jaguars.

In addition to human subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animalportrayals, for example, the ceramic ancient Olmec "Bird Vessel", and"Fish Vessel" dating to circa 1000 BC. Ceramics are produced in kilnscapable of exceeding approximately 900° C. The only other prehistoricculture known to have achieved such high temperatures is that of AncientEgypt. Bird Headed Beings.

Another type of artifact is much smaller; hardstone carvings in jade of aface in a mask form. Curators and scholars refer to "Olmec-style" facemasks as despite being Olmec in style, to date no example has beenrecovered in a archaeologically controlled Olmec context. However theyhave been recovered from sites of other cultures, including onedeliberately deposited in the ceremonial precinct of Tenochtitlan(Mexico City), which would presumably have been about 2,000 years oldwhen the Aztecs buried it, suggesting these were valued and collected asRoman antiquities were in Europe.

positions they had been found in at La Venta, Tabasco.

There is no definite answer for what this scene is enacting.

The men have elongated skulls, the result of

cranial deformation begun at an early age.

A rare depiction of a female in Olmec art, this seated figure is alsounusual for her hematite mirror ornament. Her seated pose and mirror, anemblem of political and religious authority, convey her elite status.Mirrors functioned as divination tools, providing symbolic access toother realms.

This article on the Olmec figurinedescribes a number of archetypical figurines produced by the FormativePeriod inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While many of these figurines may ormay not have been produced directly by the people of the Olmecheartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of Olmec culture.

These figurines are usually found in household refuse, in ancientconstruction fill, and (outside the Olmec heartland) in graves, althoughmany Olmec-style figurines, particularly those labelled as Las Bocas-or Xochipala-style, were recovered by looters and are therefore withoutprovenance.

The vast majority of figurines are simple in design, often nude or with aminimum of clothing, and made of local terracotta. Most of theserecoveries are mere fragments: a head, arm, torso, or a leg. It isthought, based on wooden busts recovered from the water-logged El Manatisite, that figurines were also carved from wood, but, if so, none havesurvived.

More durable and better known by the general public are those figurinescarved, usually with a degree of skill, from jade, serpentine,greenstone, basalt, and other minerals and stones.

In March 2005, a team of archaeologists used NAA (neutron activationanalysis) to compare over 1000 ancient Mesoamerican Olmec-style ceramicartifacts with 275 samples of clay so as to "fingerprint" potteryorigination. They found that "the Olmec packaged and exported theirbeliefs throughout the region in the form of specialized ceramic designsand forms, which quickly became hallmarks of elite status in variousregions of ancient Mexico.

In August 2005 another study, this time using petrography, found thatthe "exchanges of vessels between highland and lowland chiefly centerswere reciprocal, or two way." Five of the samples dug up in San Lorenzowere "unambiguously" from Oaxaca. According to one of the archaeologistsconducting the study, this "contradicts recent claims that the GulfCoast was the sole source of pottery" in Mesoamerica.

The results of the INAA study were later defended in March 2006 in twoarticles in Latin American Antiquity. Because the INAA sample is muchlarger than the petrographic sample (a total of over 1600 analyses ofraw materials and clays vs. approximately 20 pottery thin sections inthe petrographic study), the authors of the Latin American Antiquitypapers argue that the petrographic study cannot possibly overturn theINAA study.

While Olmec figurines are found abundantly in sites throughout theFormative Period, it is the stone monuments such as the colossal headsthat are the most recognizable feature of Olmec culture. These monumentscan be divided into four classes:

- Colossal heads

- Rectangular "altars" (more likely thrones)

- Free-standing in-the-round sculpture, such as the twins from El Azuzul or San Martin Pajapan Monument 1.

- Stelae, such as La Venta Monument 19 above. The stelae form was generally introduced later than the colossal heads, altars, orfree-standing sculptures. Over time stelae moved from simplerepresentation of figures, such as Monument 19 or La Venta Stela 1,toward representations of historical events, particularly actslegitimizing rulers. This trend would culminate in post-Olmec monumentssuch as La Mojarra Stela 1, which combines images of rulers with scriptand calendar dates.

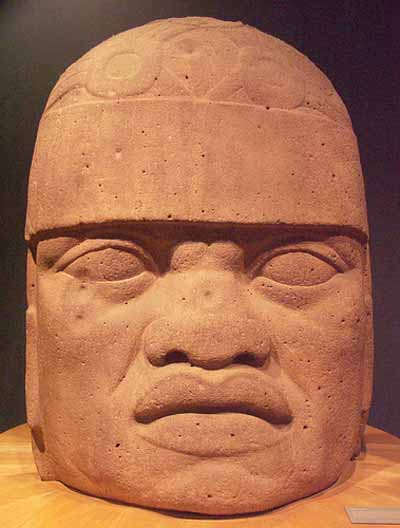

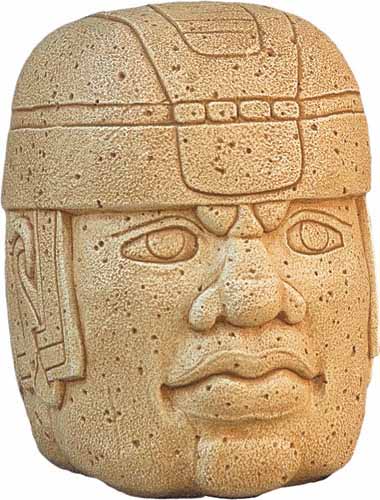

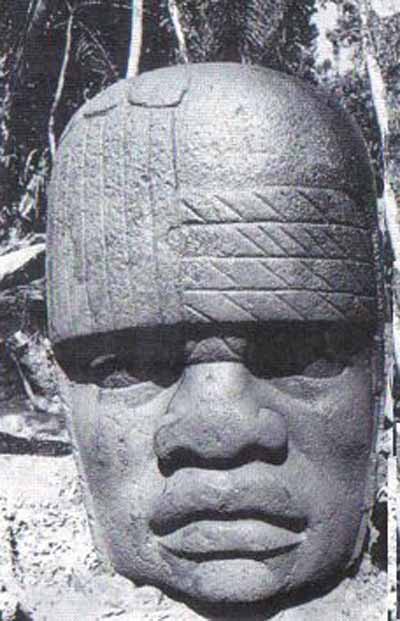

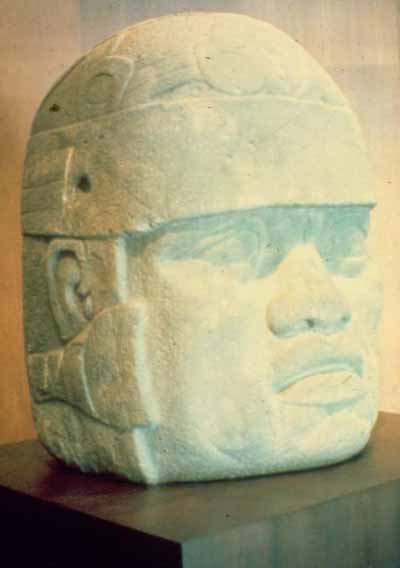

The most recognized aspect of the Olmec civilization are the enormoushelmeted heads. As no known pre-Columbian text explains them, theseimpressive monuments have been the subject of much speculation. Oncetheorized to be ballplayers, it is now generally accepted that theseheads are portraits of rulers, perhaps dressed as ballplayers. Infusedwith individuality, no two heads are alike and the helmet-likeheaddresses are adorned with distinctive elements, suggesting to somepersonal or group symbols.

In 1939 a carving was discovered near the gigantic head with acharacteristic Olmec design on one side and a date symbol on the other.This revealed a shocking truth: the Olmecs had a far greater right to beconsidered the mother culture. Hundreds of years earlier than anyonehad imagined, simple villages had given way to a complex societygoverned by kings and priests, with impressive ceremonial centers andartworks. Today many find the term "mother culture" misleading, butclearly the Olmecs came first.

Other megalithic heads were discovered in the intervening years, allwith African facial features. This is not necessarily to suggest thatthe founders or leaders of Olmec civilization came directly from Africa,since many original populations of countries like Cambodia and thePhilippines have similar characteristics. These might have been broughtalong when the first humans entered the Americas from Asia.

Many Olmec heads had the symbol of the jaguar in different headpieces.The jaguar is a potent symbol that represents the Mesoamerican cultures.The olmec used the shaman during a sacred ritual to transform into ajaguar. They believe that the jaguar was the living and the dead. Alsothey thought the olmec clearly imaged that their shamans transformed onritual occasions into a perfect structure that was very important tothem. They thought that was important for the gods, ritual, and myths.

Site Count Designations San Lorenzo 10 Colossal Heads 1 through 10 La Venta 4 Monuments 1 through 4 Tres Zapotes 2 Monuments A & Q Rancho la Cobata 1 Monument 1

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Cobata head, at 3.4 m high,to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m. It has been calculated that thelargest heads weigh between 25 and 55 short tons (50 t).

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt,found in the Tuxtlas Mountains. The Tres Zapotes heads, for example,were sculpted from basalt found at the summit of Cerro el Vigía, at thewestern end of the Tuxtlas. The San Lorenzo and La Venta heads, on theother hand, were likely carved from the basalt of Cerro Cintepec, on thesoutheastern side, perhaps at the nearby Llano del Jicaro workshop, anddragged or floated to their final destination dozens of miles away. Ithas been estimated that moving a colossal head required the efforts of1,500 people for three to four months.

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variouslymutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/orreburied. It is known that some monuments, and at least two heads, wererecycled or recarved, but it is not known whether this was simply due tothe scarcity of stone or whether these actions had ritual or otherconnotations. It is also suspected that some mutilation had significancebeyond mere destruction, but some scholars still do not rule outinternal conflicts or, less likely, invasion as a factor.

Almost all of these colossal heads bear the same features, flattenednose, wide lips, and capping headpiece, possible features of the Olmecwarrior-kings. These characteristics have caused some debate due totheir apparent resemblance to African facial characteristics. Based onthis comparison, some have insisted that the Olmecs were Africans whohad emigrated to the New World. However, claims of pre-Columbiancontacts with Africa are rejected by the vast majority of archeologistsand other Mesoamerican scholars.

Explanations for the facial features of the colossal heads include thepossibility that the heads were carved in this manner due to the shallowspace allowed on the basalt boulders. Others note that in addition tothe broad noses and thick lips, the heads have the Asian eye-fold, andthat all these characteristics can still be found in modern MesoamericanIndians. To support this, in the 1940s artist/art historian MiguelCovarrubias published a series of photos of Olmec artworks and of thefaces of modern Mexican Indians with very similar facialcharacteristics. In addition, the African origin hypothesis assumes thatOlmec carving was intended to be realistic, an assumption that is hardto justify given the full corpus of representation in Olmec carving.

"The Grandmother", Monument 5 at La Venta

Monument 1, one of the four Olmec colossal heads at

Museo de Antropología de Xalapa in Xalapa, Veracruz.

This head dates from 1200 to 900 BCE

and is 2.9 meters high and 2.1 meters wide.

Monuments were also an important characteristic of Olmec centers. Todaythey provide us with some idea of the nature of Olmec ideology. Thecolossal heads are commanding portraits of individual Olmec rulers, andthe large symbol displayed on the 'helmet' of each colossal head appearsto be an identification motif for that person.Colossal heads glorified the rulers while they were alive, andcommemorated them as revered ancestors after their death.

Replies

Wow, that was amazing information and research.That's why I like this discussion group you actually can learn lots of about the ancients and ways and understandings.I learn myself from the posts..............that's cool.

Sunrise thanks for what you do.

Thank You,James a lot for appreciation and kind words!I'm happy,that I can bring information to such a people like you,who lives and breath with this...

Love and Light!

Sunrise

The discovery of a fist-sized ceramic cylinder and fragments of engraved plaques has pushed back the earliest evidence of writing in the Americas by at least 350 years to 650 BC. Rolling the cylinder printed symbols indicating allegiance to a king, a striking difference from the Old World, where the oldest known writing was used for keeping records by the first accountants. Archaeologists uncovered the cylinder and fingernail-sized fragments among debris from an ancient festival at San Andres, an Olmec town on the coastal plain of the Mexican state of Tabasco. Carbon dating of layers in the rubbish heap gave age of the artefacts.

The next-oldest writing from the region is on a monument at a site of the Zapotec culture 300 kilometres to the west. But its date is poorly constrained, to sometime between 300 BC and 200 AD. Three later cultures in the same area used similar writing, the well-known Mayan, and the lesser-known Isthmain and Oxacan. The cylinder shows two glyphs linked by lines to the mouth of a bird, giving the impression the glyphs are being spoken. One is "ajaw," meaning "king," and the other "three ajaw", a day in the sacred 260-day calendar used throughout the region for over a millennium. Later cultures used similar lines to show speech by people as well as by animals. When covered with ink or paint, the roller printed the bird and symbols on cloth or people's bodies. The date probably was the king's name, a common practice at the time."It's a kind of royal seal, used in decoration," Mary Pohl, an anthropologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, told New Scientist. People in San Andres probably wore it "to show their fealty to the king" who resided at the main Olmec city of La Venta nearby.

The Olmec were the first American culture with a distinct ruling class, and Pohl believes they developed writing for rituals and rulers. Later Mesoamerican writing retained the links to kings and rituals, including the sacred calendar. Pohl says that writing could have originated at the start of the first Olmec culture in 1300 BC, but no evidence has survived. In contrast, Old World writing is far older and traces back to tokens placed in clay envelopes to keep account of animals or other possessions. By about 3000 BC, symbols written on tablets replaced the tokens, becoming the world's first writing.

Scientists Solve Jade Source Mystery - June 2002, World Scientist

Since the 18th century, collectors, geologists and archaeologists have sought the answer to a frustrating mystery: The ancient Olmecs fashioned statues out of striking blue-green jade, but the stone itself was nowhere to be found in the Americas. Now scientists believe they have discovered the source, a mother lode of jade in Guatemala that could tell much about ancient American civilizations and about the formation of the continent where they lived. Ever since Alexander von Humboldt began collecting jade in Latin America in the 18th century, Olmec-style statuettes and axes, crafted more than two millennia ago, had been found from Mexico to Costa Rica. But never had that kind of jade been seen naturally in any quantity in the area. Then in 1999, Russell Seitz, a geophysicist who had spent 23 years searching for the source of Olmec jade, took his fiancee to the colonial city of Antigua in central Guatemala. On the roof of a store, he found jade that was vastly different from the opaque jade he had seen in Mexico and Central America, and it was identical to the translucent blue-green stones so coveted by the Olmecs, who lived in central and southern Mexico from 1000-400 B.C.

While the actual ethno-linguistic affiliation of the Olmec remain unknown, various hypotheses have been put forward. For example, in 1968 Michael D. Coe speculated that the Olmec were Mayan predecessors.

In 1976 linguists Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman published a paper in which they argued a core number of loanwords had apparently spread from a Mixe-Zoquean language into many other Mesoamerican languages.

Campbell and Kaufman proposed that the presence of these core loanwords indicated that the Olmec generally regarded as the first "highly civilized" Mesoamerican society - spoke a language ancestral to Mixe-Zoquean. The spread of this vocabulary particular to their culture accompanied the diffusion of other Olmec cultural and artistic traits that appears in the archaeological record of other Mesoamerican societies.

Mixe-Zoque specialist Søren Wichmann first critiqued this theory on the basis that most of the Mixe-Zoquean loans seemed to originate from the Zoquean branch of the family only. This implied the loanword transmission occurred in the period after the two branches of the language family split, placing the time of the borrowings outside of the Olmec period. However new evidence has pushed back the proposed date for the split of Mixean and Zoquean languages to a period within the Olmec era.

Based on this dating, the architectural and archaeological patterns and the particulars of the vocabulary loaned to other Mesoamerican languages from Mixe-Zoquean, Wichmann now suggests that the Olmecs of San Lorenzo spoke proto-Mixe and the Olmecs of La Venta spoke proto-Zoque.

At least the fact that the Mixe-Zoquean languages still are, and are historically known to have been, spoken in an area corresponding roughly to the Olmec heartland, leads most scholars to assume that the Olmec spoke one or more Mixe-Zoquean languages.

Social and Political Organization

Little is directly known about the societal or political structure of Olmec society. Although it is assumed by most researchers that the colossal heads and several other sculptures represent rulers, nothing has been found like the Maya stelae which name specific rulers and provide the dates of their rule.

Instead, archaeologists relied on the data that they had, such as large- and small-scale site surveys. These provided evidence of considerable centralization within the Olmec region, first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta no other Olmec sites come close to these in terms of area or in the quantity and quality of architecture and sculpture.

This evidence of geographic and demographic centralization leads archaeologists to propose that Olmec society itself was hierarchial, concentrated first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta, with an elite that was able to use their control over materials such as water and monumental stone to exert command and legitimize their regime.

Nonetheless, Olmec society is thought to lack many of the institutions of later civilizations, such as a standing army or priestly caste. And there is no evidence that San Lorenzo or La Venta controlled, even during their heyday, all of the Olmec heartland. There is some doubt, for example, that La Venta controlled even Arroyo Sonso, only some 35 km away. Studies of the Tuxtla Mountain settlements, some 60 km away, indicate that this area was composed of more or less egalitarian communities outside the control of lowland centers.

Trade

The wide diffusion of Olmec artifacts and "Olmecoid" iconography throughout much of Mesoamerica indicates the existence of extensive long-distance trade networks. Exotic, prestigious and high-value materials such as greenstone and marine shell were moved in significant quantities across large distances. While the Olmec were not the first in Mesoamerica to organise long-distance exchanges of goods, the Olmec period saw a significant expansion in interregional trade routes, more variety in material goods exchanged and a greater diversity in the sources from which the base materials were obtained.

Village Life and Diet

Despite their size, San Lorenzo and La Venta were largely ceremonial centers, and the majority of the Olmec lived in villages similar to present-day villages and hamlets in Tabasco and Veracruz.

These villages were located on higher ground and consisted of several scattered houses. A modest temple may have been associated with the larger villages. The individual dwellings would consist of a house, an associated lean-to, and one or more storage pits (similar in function to a root cellar). A nearby garden was used for medicinal and cooking herbs and for smaller crops such as the domesticated sunflower. Fruit trees, such as avocado or cacao, were likely available nearby.

Although the river banks were used to plant crops between flooding periods, the Olmecs also likely practiced swidden (or slash-and-burn) agriculture to clear the forests and shrubs, and to provide new fields once the old fields were exhausted.

Fields were located outside the village, and were used for maize, beans, squash, manioc, sweet potato, as well as cotton. Based on archaeological studies of two villages in the Tuxtlas Mountains, it is known that maize cultivation became increasingly important to the Olmec over time, although the diet remained fairly diverse.

The fruits and vegetables were supplemented with fish, turtle, snake, and mollusks from the nearby rivers, and crabs and shellfish in the coastal areas. Birds were available as food sources, as were game including peccary, opossum, raccoon, rabbit, and in particular deer. Despite the wide range of hunting and fishing available, midden surveys in San Lorenzo have found that the domesticated dog was the single most plentiful source of animal protein.

Etymology

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec, and was the Aztec name for the people who lived in the Gulf Lowlands in the 15th and 16th centuries, some 2000 years after the Olmec culture died out. The term "rubber people" refers to the ancient practice, spanning from ancient Olmecs to Aztecs, of extracting latex from Castilla elastica, a rubber tree in the area. The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create rubber as early as 1600 BCE.

Early modern explorers and archaeologists, however, mistakenly applied the name "Olmec" to the rediscovered ruins and artifacts in the heartland decades before it was understood that these were not created by people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec", but rather a culture that was 2000 years older. Despite the mistaken identity, the name has stuck.

It is not known what name the ancient Olmec used for themselves; some later Mesoamerican accounts seem to refer to the ancient Olmec as "Tamoanchan". A contemporary term sometimes used to describe the Olmec culture is tenocelome, meaning "mouth of the jaguar".

History of Scholarly Research

Olmec culture was unknown to historians until the mid-19th century. In 1869 the Mexican antiquarian traveller José Melgar y Serrano published a description of the first Olmec monument to have been found in situ. This monument - the colossal head now labelled Tres Zapotes Monument A - had been discovered in the late 1850s by a farm worker clearing forested land on a hacienda in Veracruz.

Hearing about the curious find while traveling through the region, Melgar y Serrano first visited the site in 1862 to see for himself and complete partially exposed sculpture's excavation. His description of the object, published several years later after further visits to the site, represents the earliest documented report of an artifact of what is now known as the Olmec culture.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Olmec artifacts such as the Kunz Axe (right) came to light and were subsequently recognized as belonging to a unique artistic tradition.

Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge made the first detailed descriptions of La Venta and San Martin Pajapan Monument 1 during their 1925 expedition. However, at this time most archaeologists assumed the Olmec were contemporaneous with the Maya even Blom and La Farge were, in their own words, "inclined to ascribe them to the Maya culture".

Matthew Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution conducted the first detailed scientific excavations of Olmec sites in the 1930s and 1940s. Stirling, along with art historian Miguel Covarrubias, became convinced that the Olmec predated most other known Mesoamerican civilizations.

In counterpoint to Stirling, Covarrubias, and Alfonso Caso, however, Mayanists Eric Thompson and Sylvanus Morley argued for Classic-era dates for the Olmec artifacts. The question of Olmec chronology came to a head at a 1942 Tuxtla Gutierrez conference, where Alfonso Caso declared that the Olmecs were the "mother culture" ("cultura madre") of Mesoamerica.

Shortly after the conference, radiocarbon dating proved the antiquity of the Olmec civilization, although the "mother culture" question generates much debate even 60 years later.

About 3,000 years ago, elders and leaders in farming communities of Mesoamerica established a shared vision of their world. These sages of Olmec civilization etched their creed on polished stone artifacts and then rubbed red paint into the patterns. This is a code that could be read by any sage who knew the religion. This plaque reords the story of creation. It shows the World Tree sprouting out of Creation Mountain at the Three-Stone-Place the center of the night sky, the renewed sky, the mountian and the renewed earth, and the Three-Stone-Place the hearth, the place of First Father's rebirth as Maize.

It confirms the tradition recorded by:

* Friar Diego de Landa that the Olmec people made twelve migrations to the New World.

* Famous Mayan historian Ixtlixochitl, that the Olmec came to Mexico in "ships of barks " and landed at Pontochan, which they commenced to populate

These Blacks are frequently depicted in the Mayan books/writings carrying trade goods. The tree depicts seven branches and twelve roots. The seven branches probably represent the seven major clans of the Olmec people. The twelve roots extending into the water from the boat probably signifies the "twelve roads through the sea", mentioned by Friar Diego Landa.

Another Version of the Tree of Life

The Eye of Creation and the Snake or Human DNA

Writing

The Olmec may have been the first civilization in the Western Hemisphere to develop a writing system. Symbols found in 2002 and 2006 date to 650 BCE and 900 BCE respectively, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BCE.

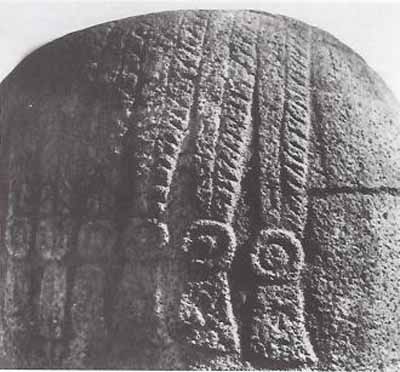

The 2002 find at the San Andrés site shows a bird, speech scrolls, and glyphs that are similar to the later Mayan hieroglyphs. Known as the Cascajal Block, the 2006 find from a site near San Lorenzo, shows a set of 62 symbols, 28 of which are unique, carved on a serpentine block. A large number of prominent archaeologists have hailed this find as the "earliest pre-Columbian writing". Others are skeptical because of the stone's singularity, the fact that it had been removed from any archaeological context, and because it bears no apparent resemblance to any other Mesoamerican writing system.

There are also well-documented later hieroglyphs known as "Epi-Olmec," and while there are some who believe that Epi-Olmec may represent a transitional script between an earlier Olmec writing system and Mayan writing, the matter remains unsettled.

The Olmec image of the rain spirit appears frequently in the mythology of succeeding cultures. Invariably the rain spirit is male, though he may have a wife who shares authority over the waters. Often he is perceived as a child or a young man, sometimes as a dwarf. He may also be portrayed as a powerful rain god, with many helpers.

In Aztec and Maya traditions, the rain lord is a master spirit, attended by several helpers. His name in the Aztec language is Tlaloc, and his helpers are "tlaloque." The Maya of the Yucatan recognize Chaac and the "chacs." In the Guatemalan area, these spirits are often associated with gods of thunder and lightning as well as with rain. The rain spirits are known as Mam and the "mams" among the Mopan of Belize. In some traditions, as with the Pipil of El Salvador, the figure of the master is missing, and the myths focus on "rain children," or "rain boys." Modern Nahua consider these numerous spirits to be dwarfs, or "little people." In the state of Chiapas, the Zoque people report that the rain spirits are very old but look like boys.

The Olmecs are believed to be one of the first tribes to engage in Shamanistic rituals. The Olmec Tribe believed that the Jaquar was a rain deity and fertility diety. The Jaquar was chosen because the Olmecs believed it was the most powerful and feared animal. They also believed that the Jaquar was an Avatar of the living and the dead. The men would sacrifice blood to the jaguar, wear masks, dance, and crack whips to imitate the sound of thunder. This ritual was done in May. The Olmec also made offerings of jade figures to the jaguar. The Olmecs made numerous statues representing "Were, Jaquar " men. These men are normally shown with grimacing Jaquar facial features with Human bodies. They are believed to be men , of the Olmec tribe, that are transforming into the Jaquar. One of these transforming Shamans can be seen in the statue "Crouching figure of a Man-Jaquar".

It is an almost black, little figurine of a man rising from one knee in the ecstasy of transformation. The transformation figure shows the human and feline characteristics brilliantly fused together. The head and ears remain human , but the crown of it¹s head is smooth , as if shaved. The features of it's face seem to flow into each other and the eye sockets are wide and deeply bored. Extended by incised lines above the eyes, the carved eyebrows are similar to flame eyebrows and signify the shedding of skin.

In the figurine the 'Standing figure of a Were-Jaquar' another Shaman is seen in the transformation process . This figure stands with one leg forward to counterbalance the slight torsion of the body. The arms are extended and each hand is balled into a fist, similar to a boxing stance. This Figure has almost the exact same features as the 'Crouching Figure' that represent the ecstasy of the transformation. Its hands and feet are oversized to anticipate the paws of the Jaquar.

In both figures the tortured facial features are intended to convey, not ferocity and aggressiveness, but emotional stress beyond endurance. It is precisely the sort of physically and mentally exhausting crisis, the crossing of the threshold between two worlds, to kinds of reality, if you will, that is part and practice of ecstatic Shamanism everywhere. The crossing over and transformation into the most powerful predator of the rain forest and the Savannah.

The Transformation was brought on by a series of activities which could incorporate singing or chanting to the Jaguar deity. The Shaman would dance around and chant a mantra to spirit world and would also use the rhythm of a beating. It is also believed that the Olmec would also ingest a 'mind altering' drug which would intoxicate the Shaman and make him dizzy Tobacco powder , which was also used to achieve the transformation could be inhaled directly through the nose or ground up with lime to make a chewing wad. The evidence to support this can be seen in the Hollow Figure in this statue a man is seen using a snuffing pipe made from small gourds.

The "were-jaguar " Shamans were also associated and depicted in acrobatic poses, this represents the agility of the feline. Shamans were believed to have the ability to flip backwards and transform before they had landed. There have been a number a figures found , that incorporate acrobatic poses. In the statues 'Figure with feet on head' and "vessel in the form of a contortionist". Shamans are shown in complex and complicated poses. The Shamans seems to very comfortable and achieve each pose with ease.