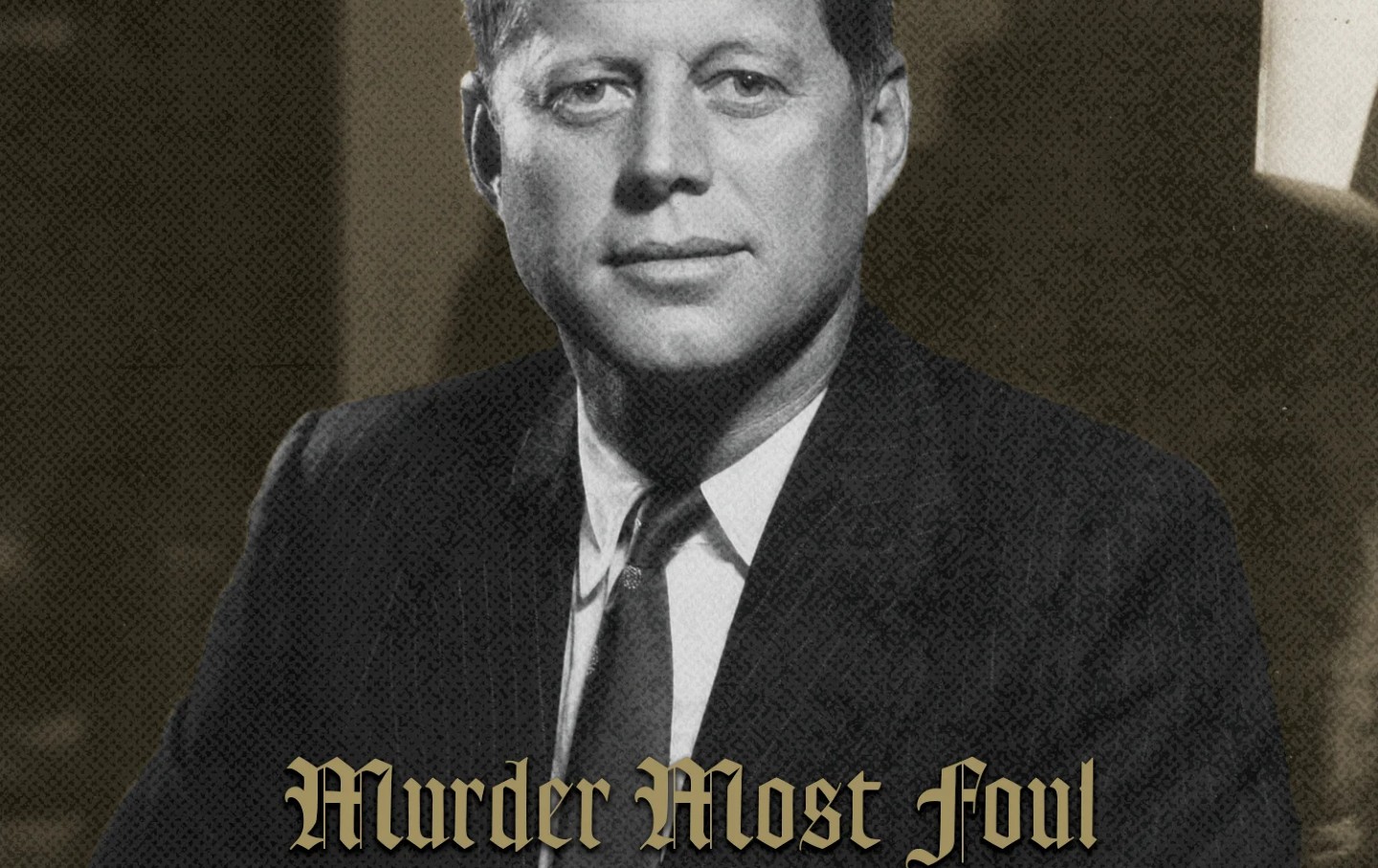

JOHN F. KENNEDY - 59 YEARS AGO

I would like to remind our readers of this date. I believe that at the time, most of you had not yet been born. Regardless of our generation have born after the 60s, this episode is a timeless milestone that, for better or for worse, stood out in the collective consciousness of later decades.

It was on April 27, 1961, that President Kennedy addresses to the American Newspaper Publishers Association, during the Bureau of Advertising dinner, held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. In this speech, the president addressed his discontent with the news coverage given by the press before, during, and after the incident in the Bay of Pigs, referring to the need for importance on public information and on state secrecy.

What follows is the full transcript of the speech.

The President and the Press

I have selected as the title of my remarks tonight “The President and the Press”. Some may suggest that this would be more naturally worded: “The President versus the Press” — but those are not my sentiments — tonight —.

It is true, however, that when a well-known diplomat from another country demanded recently that our State Department repudiate certain newspaper attacks on his colleague, it was unnecessary for us to reply that this Administration was not responsible for the press. For the press had already made it clear that it was not responsible for this Administration.

Nevertheless, my purpose here tonight is not to deliver the usual assault on the so-called one-party press. On the contrary, in recent months I have rarely heard any complaints about political bias in the press — except from a few Republicans.

Nor is it my purpose tonight to discuss or defend the televising of Presidential press conference. I think it is highly beneficial to have some 20 million Americans regularly sit in on these Conferences, to observe, if I may say so, the incisive, the intelligent, and the courteous qualities displayed… by your Washington correspondents.

Nor, finally, are these remarks intended to examine the proper degree of privacy which the press should allow to any President and his family. If in the last few months your White House reporters and photographers have been attending church services with regularity, that has surely done them no harm… On the other hand, I realized that your staff and wire service photographers may be complaining that they do not enjoy the same “green privileges” at the local golf courses which they once did. It is true that my predecessor did not object, as I do, the pictures of one’s golfing skills in action; but neither, on the other hand, did he ever “bean” a Secret Service man.

My topic tonight is a more solemn one… of concern to publishers as well as editors. I want to talk about our common responsibilities in the face of a common challenge. The events of recent weeks may have helped to illumine that challenge for some; but the dimensions of its threat have long loomed this large on our horizon. Whatever our hopes may be for the future — for reducing this threat or living with it — there is no escaping either the gravity or the totality of its challenge to our security and survival — a challenge that confronts us in unaccustomed ways in every sphere of human activity.

This deadly challenge imposes upon our society to requirements do direct concern to both the press and the President — two requirements that may seem almost contradictory in tone, but which must be reconciled and fulfilled if we are to meet this national peril. I refer, first, to the need for far greater public information; and, second, to the need for far greater official secrecy.

I

The very word “secrecy” is repugnant in a free and open republic; and we are as a people inherently and historically opposed to secret societies, to secret oaths, and to secret proceedings. We decided long ago that the dangers of excessive and unwarranted concealment of pertinent facts far outweighed the dangers which are cited to justify it. Even today, there is little value in opposing the threat of a closed society by imitating its arbitrary restrictions. Even today there is little value in insuring the survival of our nation if our traditions do not survive with it. And there is a very grave danger that an announced need for increased security will be seized upon by those anxious to expand its meaning to the very limits of official censorship and concealment.

That I do not intend to permit. And no official of my Administration, whether his rank is high or low, civilian or military, should interpret my words here tonight as an excuse to censor the news, to stifle dissent, to cover up our mistakes or to withhold from the press and the public the facts they deserve to know.

But I do ask every publisher, every editor, and every newsman in the nation to re-examine his own standards, and to recognize the nature of our country’s peril. In a time of war, the Government and the press have customarily joined in an effort, based largely on self-discipline to prevent unauthorized disclosures to the enemy. In a time of “clear and present danger”, the courts have held that even the privileged rights of the First Amendment must yield to the public’s need for national security.

Today no war has been declared — and however fierce the struggle, it may never be declared in traditional fashion. Our way of life is under attack. Those who make themselves our enemy are advancing around the globe. The survival of our friends is in danger. And yet no war has been declared, no borders have been crossed, no missiles have been fired.

If the press is awaiting a declaration of war before it imposes the self-discipline of combat conditions, then I can only say that no war ever posed a greater threat to our security. If you are awaiting a finding of “clear and present danger”, then I can only say that the danger has never been more clear and its presence has never been more imminent.

It requires a change in outlook, a change in tactics, a change in missions — by the government, by the people, by every businessman, union leader, and newspaper. For we are opposed around the world by a monolithic and ruthless conspiracy that relies primarily on covert means of expanding its sphere of influence — on infiltration instead of invasion, on subversion instead of elections, on intimidation instead of free choice, on guerrillas by night instead of armies by day. It is a system which has conscripted vast human and material resources into the building of a tightly-knit, highly efficient machine that combines military, diplomatic, intelligence, economic, scientific, and political operations.

Its preparations are concealed, not published. Its mistakes are buried, not headlined. Its dissenters are silenced, not lionized. No expenditure is questioned, no rumor is printed, no secret is revealed. It conducts the Cold War, in short, with a war-time discipline no democracy would ever hope or wish to match.

Nevertheless, every democracy recognizes the necessary restraints of national security — and the question remains whether those restraints need to be more strictly observed if we are to oppose this kind of attack as well as outright invasion.

For the facts of the matter are that this nation’s foes have openly boasted of acquiring through our newspaper information they would otherwise hire agents to acquire through theft, bribery or espionage; that details of this nation’s covert preparations to counter the enemy’s covert operations have been available to every newspaper reader, friend and foe alike; that the size, the strength, the location and the nature of our forces and weapons, and our plans and strategy for their use, have all been pinpointed in the press and other news media to a degree sufficient to satisfy any foreign power; and that, in at least one case, the publication of details concerning a secret mechanism in our possession required its alteration at the expense of considerable time and money.

The newspapers which printed these stories were loyal, patriotic, and well-meaning. Had we been engaged in open warfare, they undoubtedly would not have published such items. But in the absence of open warfare, they recognized only the tests of journalism and not the tests of national security. And my question tonight is whether additional tests should not now be adopted.

That question is for you alone to answer. No public official should answer it for you. No governmental plan should impose its restraints against your will. But I would be failing in my duty to the Nation if I did not commend this problem to your attention, and urge its thoughtful consideration.

On many earlier occasions, I have said — and your newspapers have said — that there are times that appeal to every citizen’s sense of sacrifice and self-discipline. They call out to every citizen to weigh his rights and comforts against his obligations to the national good. I cannot now believe that those citizens who serve in the newspaper business consider themselves exempt from that appeal.

I have no intention of establishing a new Office of War Information to govern the flow of news. I am not suggesting any new forms of censorship or new types of security classification. I have no easy answer to the dilemma I have posed, and would not seek to impose it if I had one. But I am asking the members of the newspaper profession and industry in this country to re-examine their own obligations — to consider the degree and the nature of the present danger — and to heed the duty of self-restraint which that danger imposes on us all.

Every newspaper now asks itself, with respect to every story: “Is it news?” All I suggest is that you add the question: “Is it in the national interest?” And I hope that every group in America — unions and businessmen and public officials at every level — will ask the same question of their endeavors, and subject their actions to this same exacting test.

And should the press of America consider and recommend the voluntary assumption of specific new steps or machinery, I can assure you that this Administration will cooperate whole-heartedly with those recommendations.

Perhaps there will be no recommendations. Perhaps there is no answer to the dilemma faced by a free open society in a cold and secret war. In times of peace, any discussion of this subject, and any action that results, are both painful and without precedent. But this is a time of peace and peril which knows no precedent in history.

II

It is unprecedented nature of this challenge that also gives rise to your second obligation — and obligation which I share. And that is our obligation to inform and alert the American people — to make certain they possess all the facts they need, and understand them as well — the perils, the prospects, the purposes of our program and the choices we face.

No President should fear public scrutiny of his program. For from that scrutiny comes understanding, and from that understanding comes support. I am not asking your newspapers to support me at all times on the editorial page — this is not Utopia yet… But I am asking your help in the tremendous task of informing and alerting the American people. For I have complete confidence in the response and dedication of our citizens whenever they are fully informed.

I not only could not stifle controversy among your readers, I welcome it. This Administration intends to be candid about its errors; for, as a wise man once said, “An error doesn’t become a mistake until you refuse to correct it.” We intend to accept full responsibility for our errors; and we expect you to point them out when we miss them.

Without debate, without criticism, no Administration can succeed — and no republic can survive. That is why the Athenian law-maker solon decreed it a crime from the citizen to shrink from controversy. And that is why our press was protected by the First Amendment — the only business in America specifically protected by the Constitution — not primarily to amuse and entertain, not to emphasize the trivial and the sentimental, not simply to “give the public what it wants” — but to inform, to arouse, to reflect, to state our dangers and our opportunities, to indicate our crises and our choices, to lead, mold, educate and sometimes even anger public opinion.

This means greater coverage and analysis of international news — for it is no longer far away and foreign but close at hand and local. It means greater attention to improved understanding of the news as well as improved transmission. And it means, finally, that the goverment, at all levels, must meet its obligation to provide you with the fullest possible information outside the very narrow limits previously mentioned — and this administration intends to meet that obligation to a degree never before approached by any nation in the world.

III

It was early in the Seventeenth Century that Francis Bacon remarked on three recent inventions already transforming the world: the compass, gunpowder and the printing press. Now the links between nations first forged by the compass have made us all citizens of one world, the hopes, and threats of one becoming the hopes and threats of all. I that one world’s efforts to live together, the evolution of gun powder to its ultimate limit has warned mankind of the terrible consequences of failure.

And so it is to the printing press — to the recorder of man’s deeds, the keeper of his conscience, the courier of his news — that we look for strength and assistance, confident that with your help man will always be what he was born to be: free and independent.

The audio version of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s speech – “The President and the Press” – April 27, 1961, before the American Association of Newspaper Editors.For we were in the early 60s, and JFK informed the American citizen about the dangers of censorship in the press, the lack of ethic, and the inconsistency of it, as its simultaneously a tool of disinformation for the public and of advantage for the enemy . It also speaks of the secret war that was never announced, but that existed. A state of transparent Governance, receptive to the population, and the importance of the citizen being actively collaborative with its critical thinking because that is part of his rights, freedoms, and duties. Physical, cultural, and linguistic differences and distances do not make us more alien to each other when the world is everyone’s home, and our link is communication.

Wearing a mask or a gag is absolutely the same thing because none protects from viruses, they only illustrate your limited freedom of speech and thought.

Wearing a mask or a gag is absolutely the same thing because none protects from viruses, they only illustrate your limited freedom of speech and thought.JFK warned us about it all… 59 years ago. After this time, what we have achieved is, perhaps figuratively, a mask on our face – synonymous of a gag – to cover our mouths. This while the silent war continues. But it is not only the rare minerals of the Earth, nor the conquest of territories. Now, the enemy wants absolute control of our minds.

May future generations never have to live the hell we went through!

~ Universal Forces

References:

~ Address – “The President and the Press,” Bureau of Advertising, American Newspaper Publishers Association, April 27, 1961:

https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKPOF/034/JFKPOF-034-021

~ Audio version – “The President and the Press,” Before The American Newspaper Publishers Association, April 27, 1961:

https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKWHA/1961/JFKWHA-025-001/JFKWHA-025-001

Comments

Dear amparo,

Like other American Presidents He must be a Member of The Secret Sociey...Free Masonry.

Sohini